Sergio Bello's function-first theory is about using functional analysis

to advance archaeological knowledge.

It has produced some fascinating and remarkable results.

Apart from its scientific revelations,

it has shown that modern archaeology

is as much about the eye of the beholder as about science.

Sergio Bello is an occasional visitor to the South Burnett.

Kingaroar interviewed him to ask about

whether his groundbreaking function-first theory

could offer any insights into the debate

about the origin of the placename Kingaroy.

The search for the origin of the name of Kingaroy moved on.

New evidence emerged about the name of Kingaroy.

It was discovered that the popular story

about Hector Munro's Kingaroy survey camp was fiction.

Sergio's observations about the name of Kingaroy

became out-of-date.

Nevertheless, the function-first theory remains as relevant

to archaeological research as ever,

so rather than delete the whole article from the website,

the editor decided just to remove the out-of-date portion

relating to the name of Kingaroy

and keep this interesting description of the function-first theory.

Many people have never heard of the function-first theory,

so kingaroar began by asking Sergio to explain the theory in an easy-to-understand way.

Greetings.

Put simply, the function-first theory looks for utilitarian functionality in archaeological observations.

Functionality is anything that would have been of practical useful everyday value to humans.

The function-first theory holds that if an ancient feature can be interpreted as having been useful

then it is almost certain that its main purpose must have been utilitarian

as opposed to being an abstract symbol.

If it can be demonstrated that a feature could have had a utilitarian functional purpose

then any speculative abstract interpretation of the feature must be incorrect if not utterly absurd.

Application of the function-first theory has led to re-interpretations that have

made many archaeologists and celebrity broadcasters look decidedly foolish.

In the absence of proof about the past, we can't go back in a time machine to take a video of what actually happened.

Instead, what we can do is gather as much information as possible and then extract everything of practical functionality from it.

The function-first theory does this - it provides us with a picture of the past that is focused on functional reality.

Generally, experience has shown that when a functional interpretation of an archaeological feature has been positively identified then,

once it has been pointed out,

to most people it seems to be obvious.

Of course, some people will never change their opinions about anything nomatter what,

so new facts and ideas just bounce off them,

but most people who are unencumbered by vested interests are able

to look independently at relevant information and form their own opinions.

Most modern archaeologists are much more careful and scientific than their predecessors,

many of whom thought nothing of destroying sites in their zeal to make new discoveries.

But some archaeologists today still seem to be imbued with the old archaeological tradition

of devising religious, ceremonial, symbolic, and socio-economic fantasies for every ancient site, artefact and culture,

often blindly ignoring functional and scientific facts.

An overall conclusion that can be drawn from the results of using the function-first theory

is that today's archaeologists use scientific methods to produce reliable observations,

but their interpretation of observations is often pretentious nonsense based on whimsy instead of facts.

The word "first" in the function-first theory refers to the order of precedence of interpretation.

Functionality should be the first priority in interpreting archaeological observations before resorting to

speculative fantasies.

There is a fashion among modern archaeologists of using the expression "making a statement".

This unscientific concept is used to justify modern sociological ideas

as being the keys to interpreting the ancient past.

What archaeologists should be doing is considering practical functionality.

There can be no doubt that prehistoric humans

were more attuned to the functional realities of their world

than today's humans who have a vast array of knowledge at their fingertips

but who typically spend most of their time focused on fiction.

The function-first theory is in some ways just another name for functional analysis,

but as long as mainstream archaeology insists on giving cultural revisionism and personal whims

a higher priority than functional analysis

then there is a need for a formal theory

that identifies and solves this fundamental archaeological error.

For anybody who wishes to perform functional analysis,

it is almost essential for that person to have a practical knowledge of engineering

and considerable experience of constructing useful objects using nothing more than brainpower and simple materials.

Nomatter what archaeological qualifications a person may have,

if a person lacks the level of functional skills such as prehistoric humans probably possessed

then the person should face up to the fact that they are probably not competent to perform functional analysis on anything.

The function-first theory mainly reveals functional or technological insights.

Interestingly, the theory has also thrown up a few profound sociological conclusions.

For example, where functionality is concerned,

the very necessity to have to point out the bleeding obvious to most modern humans suggests that

practical functional abilities are declining.

Perhaps this is because in modern societies

the fruits of technology arrive ready-made

and don't require the operator to know much more than where the on-off switch is.

Specialisation of roles within human societies allows individuals to excel in narrow fields of expertise,

to the benefit of society as a whole.

But when the highly-paid important leaders in any particular field

don't have a clue about anything outside their narrow specialisation

then the mechanisms of specialisation within society must be deemed to have broken down.

Standards in the modern world, in many fields of endeavour, appear to

have drifted so much that the level of competence of some of society's most important players is

now equivalent to the principal dancer in a ballet company having no arms and three left feet.

It can be generally inferred from the results of the function-first theory that modern cultures

must be moving in a direction that is guaranteed to fail,

for the simple reason that the theory has shown that in modern cultures people

who in past times would have been regarded as incompetent idiots

now get to the top and thrive there.

This finding may assist historians in the study of the causes of collapse of civilisations.

Now, where was I?

Oh yes, getting back to technology-oriented functional observations,

here are some actual archaeological examples to illustrate how the function-first theory works:-

Example 1

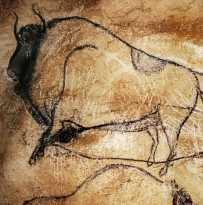

Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in France

The first example of the application of the function-first theory I would like to describe is relatively simple.

The Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in France

contains rock art dated to thirty-two thousand years ago,

hidden by a rockfall more than twenty thousand years ago that completely closed off the cave.

When the cave was discovered in 1994,

a large rock resembling a table with a horizontal top was found on the floor of the cave.

The skull of a bear was resting on the flat-topped rock.

There are prehistoric drawings of animals on the walls of the cave

and, as there are no other bones of a bear near the rock,

it is fairly certain that the skull was probably placed on the rock by the hand of a prehistoric human.

But modern archaeology goes much further, postulating that the rock may have been an altar thus proving that the humans who painted

the animals on the wall of the cave must have had religious beliefs.

The commentary in a recent documentary even said that

"Fragments of charcoal were found, potentially used as incense."

Functional analysis recognises that fire was functionally useful in many ways

that were more important than burning incense.

In this particular case, there does not even seem to be any evidence of incense.

Functional analysis reveals simply that the prehistoric humans who used the cave used fire, understood gravity

and used a table-like rock because it was useful for putting things on,

in the same way that tables are useful today.

The function-first theory recognises that the true purpose of a person putting an object on a table

tens of thousands of years ago is unlikely to be knowable today,

whereas modern archaeology indulges in make-believe

that reflects nothing more than the whims of researchers.

Based on a bear's skull resting on a rock,

archaeologists have concluded that the cave was used for ceremonies,

that the rock was an altar,

and that the users of the cave had a religion or had spiritual beliefs.

There is not the slightest scientific evidence for any of this.

A spinoff conclusion from this example is that the possession and use of modern hi-tech scientific equipment does not

automatically endow modern humans with any understanding of science whatsoever.

Example 2

Ness of Brodgar in the Orkneys

My second example of the function-first theory debunks a recent archaeological theory that

high stone walls built about 5,000 years ago were a temple complex.

The structure was discovered in 2002 at the Ness of Brodgar, a remote location in the Orkneys

on a narrow spit of land running northwest-southeast between two lochs.

Apart from its remarkable age,

the most unusual feature of the site is the high stone wall

that surrounded dozens of roofed buildings.

The site appears to have been a walled settlement.

The walls were more than three metres high.

Five thousand years ago, the weather at that exposed location was probably

similar to today, with frequent strong winds, lots of rain and very cold in winter.

Cold temperatures are exacerbated by strong winds and driving rain.

From a functional analysis of these facts,

it can be deduced that the primary purpose of the high walls

was probably as a windbreak to provide protection from frequent atrocious weather.

Within the windbreak, humans could do all manner of useful things

that would otherwise have been difficult or impossible to do for much of the time at that exposed location.

There is of course also the traditional defensive reason for high outer walls.

As well as occasional mention of a "very strong wind" by visitors to the area,

there is scientific evidence that supports the functional observation

that the high outer walls were probably built as a windbreak for a settlement.

Reconstructions of the high outer walls show that they extended right around the settlement, with a gateway at each end.

The size of the four-metre thick wall at the northwestern end, known as the "great wall of Brodgar",

is bigger than the two-metre thick "lesser wall of Brodgar" at the southeastern end.

This suggests that the northwestern wall was probably also taller than the southeastern wall.

Much of the wind and rain in the Orkneys comes in off the Atlantic Ocean to the west.

Northerly winds bring cold temperatures from the Arctic.

Therefore it appears that the differing sizes of the walls at each end of the settlement

are geographically a good fit to the prevailing weather.

A documentary about the supposed temple has been screened on television.

The celebrity archaeologist who hosted the documentary even commented that

"The locals call Orkney a place between the wind and the water",

but neither he nor any other professional archaeologist

appears to have ever noticed the undeniable functional connection

between the Ness of Brodgar's high stone walls and local weather conditions.

The main building and perhaps parts of the high stone walls were destroyed about 4,300 years ago.

Evidence of deliberate destruction has been tweaked to help prove the temple theory,

by imaginative invention of a religious purpose in destroying the walls at the end of the stone-age.

Another reason that supposedly supports the temple theory is that bones have been found that indicate that more than 600 cattle were slaughtered

at approximately the same time that the walls were destroyed,

with little weathering of the bones which indicates that the bones were covered over soon after slaughter.

The documentary pointed out that one cow can provide more than 200 meals.

So, according to archaeologists,

"600 head of cattle, enough to feed ten thousand people, all being slaughtered in a single ritual event",

"a funeral feast for the death of the temple complex itself",

thus proving conclusively that the Ness of Brodgar must have been a temple complex.

There are many problems with this absurdly unscientific theory.

For a start, if archaeologists knew anything about arithmetic then they would know that 600 times 200 makes 120,000, not 10,000.

If 600 cattle had been consumed in one feast then up to 120,000 people could have taken part,

so it is a complete mystery where the archaeological figure of 10,000 ritual feasters comes from

and it is a complete mystery why that figure would be significant anyway.

There are plenty of real functional circumstances in which walls can get destroyed

without having to fabricate esoteric religious explanations.

By applying some functional analysis,

it becomes clear that the cattle bones could have retained their unweathered state

simply by being deposited systematically over a period of a few months.

To take just one example, a group of 1,000 persons could have scoffed

600 cattle at a rate of 5 to 10 cattle per day over a period of 60 to 120 days.

So, using functional analysis, it can be shown quite reasonably that professional raiders

could have arrived out of the blue for a pillaging season,

occupied the region's main settlement with its high outer walls that were excellent windbreaks,

pillaged the region including stealing more than 600 cattle,

and then departed when the plundering of the region was complete.

Either the raiders destroyed the buildings and walls before they left,

perhaps using captives as slave labour,

or the unfortunate pillaged people destroyed their own settlement for functional reasons after the invaders had left.

This would have deprived the raiders of a comfortable base in the likely event of an unstoppable repeat raid

and it would have prevented the accumulation of the region's wealth in one place

that would otherwise have presented an irresistible target to raiders.

Given the timing of the destruction at the end of the stone-age,

it could even have happened that the raiders were from a more-advanced culture to the south,

with bronze-age technology such as swords and armour which might have given them

a decisive military advantage over the local warriors who only had stone-age weapons.

Interestingly, several broken stone-age weapons have been found at the site.

Successful pillaging is a functionally more plausible activity

than is the peculiar activity of ritually destroying one's own walls.

Pillaging raids are known to have happened throughout recorded history,

and there is certainly evidence of widespread seaborne raiding elsewhere just a few hundred years later,

whereas the temple theory with its single grandiose feast event

associated with the ceremonial destruction of useful walls by their owners

has zero functional probability and no historical authenticity.

There is no proof at all for the temple theory

which is based on an assumption that is a flight of fancy.

The foundations of the temple complex theory are as scientifically solid

as the script of a B-grade movie.

Although there is no proof for the raider theory either,

it is based on practical functionality

and it is a good fit to the scientific evidence and to historical antecedents.

The raider theory is just one of many possible causes of destruction that are functionally plausible.

Other possibilities, perhaps in combination,

include civil wars, inter-clan wars, rivalries for dynastic succession and earthquakes.

Anyway, once it has been functionally established that the high walls were probably built as a windbreak around a settlement,

and not built as the outer walls of a temple complex,

then the circumstances under which the walls were destroyed become of only secondary importance

because so far there is insufficient scientific evidence to draw any definite conclusions

about what caused the destruction.

Example 3

El Castillo Cave in Spain

My third example of the application of the function-first theory is a visual delight.

The real beauty of this example is that it enables people to test for themselves whether they see the world through the

eyes of an archaeologist or through the eyes of an engineer.

Have a look at this image.

It is part of a collection of prehistoric art from the

El Castillo Cave in Spain.

The cave contains many images that have been interpreted by archaeologists as abstract symbolism.

The cave art also includes drawings of deer, bison, horned ibex and aurochs,

so it is certain that some of the prehistoric people who used the cave drew pictures of real things.

Can you see a small boat on the right?

Is it floating in a river with water flow represented by dots?

Some of the dots are actually small circles that could represent the trajectories of bubbles or floating leaves.

Is the aerofoil shape on the left a sail?

By applying functional analysis, a boat on a river can be identified, associated with an aerofoil.

If any of this is correct then there are so many implications that

there isn't the time or space to even attempt to list them here.

So, although there is much more that I would like to talk about,

I will restrict this discussion to things related to the function-first theory.

Some archaeologists seem to assume that they have a perfect ability

to always recognise what a prehistoric object was,

and if they can't recognise what the object was

then they seem to automatically assume that the object must be an abstract symbol.

As far as I have been able to ascertain,

the official archaeological interpretation of the picture shown here

is that it contains only abstract symbols.

It appears that no archaeologists have identified any recognisable objects

in the El Castillo cave paintings other than images of animals.

An archaeologist has stated about the El Castillo images

"I don't see why they couldn't be clan signs

or some sort of affiliation marker".

The archaeologist thought that the images began as rectangles divided into sections,

and then developed this theme further until

"the individual configurations may then represent different families or groups."

This clan marker rectangle theory seems to reflect an outlook that is more bureaucratic than functional.

However, complex images that include curved lines

could not have been intended to be rectangles divided into sections,

because pronounced curves

must have been functionally intended to precisely depict shapes that have representational significance.

So the elaborate clan marker rectangle theory

falls flat on its face at the first hurdle.

This functional observation is supported by the presence in the cave of animal images

which are proof that some local prehistoric artists definitely intended curved lines to be exactly so curved.

What do you see here?

Do you see clan markers or a boat or perhaps something else that nobody has yet recognised?

These are just three of many examples.

I hope that they provide a clear picture of the function-first theory.

Archaeologists should use functional analysis as their first tool of choice in their interpretation of archaeological observations,

if they are able to.